02.11.2009

02.11.2009 A Look at US Airline CEO Compensation Through a Different Lens

'Tis the season when we will begin buying tickets to the Fourth Annual US Airline Executive Compensation Kabuki Dance. The airline dance follows the US CEO Kabuki Ball that has been playing out on Wall Street since the T.A.R.P. monies began to fill the coffers at many investment banks. Then we learned that some $18 billion of those taxpayer monies were used to pay executive bonuses in a year where the US banks clearly underperformed. Yes the Wall Street number starts with B.

Ever wonder whether: if the bankers had worked half time would they have lost only half as much? And based on losing half as much, they probably would have made more than the $18 billion. But I digress . .

Last week, Andrew Compart writing on Aviation Week’s blog, Things With Wings, posted a piece entitled Executive Pay And U.S. Airlines. After reading Mr. Compart’s piece, I was left wanting more – a deeper look at airline CEO compensation.

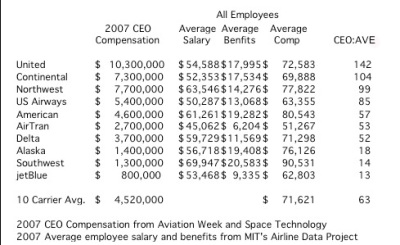

According to the Institute for Policy Studies and United for a Fair Economy, the ratio between the average compensation of U.S. CEOs and the average income of U.S. workers was 344-to-1 in 2007. How, then, does CEO pay in the US airline industry compare to compensation for airline employees?

In Mr. Compart’s analysis of executive pay at the 10 major US airlines operating independently at year-end 2007, he includes among executives’ salaries, bonuses, stock awards, stock options, payments to savings plans, and other income and rewards reported in federal filings. As Mr. Compart points out, a CEO’s salary typically accounts for only 20 percent of his or her total compensation.

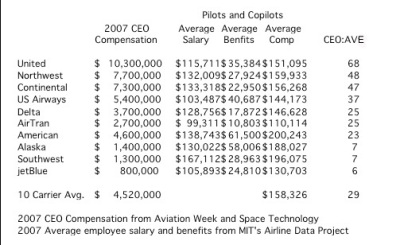

I turned to MIT’s Airline Data Project to explore a bigger picture, looking at average salary and benefit packages for each the employee and pilot workgroups at the same 10 airlines. Then I did a simple ratio analysis by company. One technical note: per diem pay should have been included for any employee groups that receive it; however the way this date is reported makes it impossible to do an exact accounting. Therefore, per diem expense is excluded for employees and pilots and would have been included in other compensation for the CEO.

In 2007, CEO compensation ranged from a high of $10.3 million at United to a low of $800,000 at jetBlue. At $10.3 million Glenn Tilton’s pay is 142 times that of the average worker at United. The 142 multiple is 41 percent of the average multiple of 344 experienced across all US industry in 2007. The simple average for the 10 airline grouping was 63 times the average airline worker, or 18 percent of US multiple of 344.

The employees at Southwest and American have the highest average employee compensation among the airlines studied, with ratios at 14 and 57 respectively. Of the six legacy carriers operating in 2007, Delta had the lowest ratio of CEO compensation at 52 – a year when Gerry Grinstein passed the gavel to Richard Anderson. Among the LCCs, AirTran had the highest ratio at 53 times. It is interesting to note that in 1980, the multiple of CEO compensation to average worker compensation was 40.

Among pilot groups, United’s CEO compensation was 68 times that of the average United pilot’s compensation. The average for the 10 airline group was 29 times. jetBlue had the lowest at 6 times, a year when Dave Barger replaced founder David Neeleman as CEO. Among the legacy carriers, American had the lowest ratio of CEO compensation to average pilot compensation at 23 times.

Concluding Thoughts

The relationship of executive compensation to worker compensation has been a measure used for decades by those on both sides of the “is it fair?” debate. I am not trying to answer that question. What is relevant is the perspective and context as it pertains to the US airline industry. It is right that airline executives have a large performance component of their compensation.

CEO and executive compensation is volatile in part because the money a proxy officer pockets is risk-based and therefore highly dependent on market conditions. Most employee compensation, by contrast, is guaranteed and has very little risk so the denominator (employee pay) does not deviate to the extent that the numerator (executive pay) does.

If nothing else, this simple analysis underscores what I’ve long preached: on balance, jobs in the airline industry pay quite well as they relate to jobs that require similar training and experience across the employment spectrum. And too often, that fact gets lost in the debate.